The Haunting Poignance of ‘The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas’ by Ursula K. Le Guin

Omelas and Zionism

Over the past twelve months, the world has witnessed an increasingly catastrophic and genocidal mission in the Middle East. The military forces of an occupied settler colony have had the relentless support of some of the western world’s leaders, whilst the innocent have been slaughtered in the tens of thousands (at the very least), and those surviving are subject to horrific crimes against humanity. Regional violence has escalated to a scale I seldom thought possible. The dream of a murderous regime to invade not only the nation of Palestine, but its neighbouring countries also, was a delusion of grandeur, or so I thought. Disturbingly, this vision has become a literal nightmare. A day hasn’t gone by in which I’ve not thought about the situation, nor have I forgotten to be grateful for the life I have and its abundant opportunities. Observing the ensuing disaster from a distance has at moments left me feeling an unendurable helplessness that I know many reading this will likely have felt too. Donating and fundraising have been the limits of any tangible aid we can provide at such a distance, and I fear that gestures of financial support are declining as time passes. I don’t believe that society as a whole is becoming numb to the issue in discussion, but I think I see a decline in the engagement with it. It is a challenge to remain engaged with the trauma of others, particularly when the rat-race is drawing you back on its gray course, or life generally presents you with a full itinerary, not to mention the personal battles we each need to combat. Nonetheless, we must strive to remain invested in the lives of others suffering needlessly and implore ourselves to find vigor enough to sustain regular acts of protest.

A story that springs to mind when I reflect on the circumstances outlined above is ‘The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas’ by Ursula K. Le Guin. I came across the short story a few months ago whilst working my way through her collection titled ‘The Wind’s Twelve Quarters’. Its familiarity was eerie and haunting. Labeled a work of philosophical fiction and published in 1973, parallels can be drawn between it and numerous global tragedies that have occurred since, and yet, the city of Omelas resembles a utilitarian, zionist-esque city like no other work I’ve read has. In the story’s foreword, Le Guin explains how the ‘central idea of this psychomyth…turns up in Dostoyevsky’s Brothers Karamazov’, and despite forgetting about it, was stunned with recognition when she came across it again in William James’ ‘The Moral Philosopher and The Moral Life’.

The James quote:

“Or if the hypothesis were offered us of a world in which Messrs. Fourier’s and Bellamy’s and Morris’s utopias should all be outdone, and millions kept permanently happy on the one simple condition that a certain lost soul on the far-off edge of things should lead a life of lonely torture, what except a sceptical and independent sort of emotion can it be which would make us immediately feel, even though an impulse arose within us to clutch at the happiness so offered, how hideous a thing would be its enjoyment when deliberately accepted as the fruit of such a bargain?”

The reference to Brothers Karamazov:

“Tell me yourself - I challenge you: let’s assume that you were called upon to build edifice of human destiny so that men would finally be happy and would find peace and tranquility. If you knew that, in order to attain this, you would have to torture just one single creature, let’s say the little girl who beat her chest so desperately in the outhouse, and that on her unavenged tears you could build that edifice, would you agree to do it? Tell me and don’t lie!”

Le Guin is no stranger to socio-political commentary, often using her science-fiction and fantasy stories to convey greater messages and pose food for thought. Omelas is no exception. Although the story lacks strong sci-fi elements that are often seen in her infamous Hainish cycle, the simplicity and familiarity of the human body and a human society are what make this work ever more disturbing. Unfortunately, you won’t understand the poignance of the story without spoiling it a bit for you, so below is an excerpt that I hope encourages you to read the story in its entirety (it's only 10 pages, linked at the end of the article) and or some of Le Guin’s other work.

As the quotes above have suggested, ‘The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas’ is a story in which an idyllic city’s existence, and the happiness of its inhabitants is entirely dependent on the entrapment and torture of a single child. Once of age, the citizens of Omelas learn about the child. Initially, many are appalled by the atrocity, though eventually most succumb to blissfully existing with the knowledge they’ve acquired. Few individuals leave the city of splendor, but those that do leave alone, with no destination in mind and never to return. Omelas is a city free of guilt, where its people believe “Happiness is based on a just discrimination of what is necessary’. What those who remain in Omelas believe necessary is this:

“In a basement under one of the beautiful public buildings of Omelas, or perhaps in the cellar of one of its spacious private homes, there is a room. It has one locked door, and no window. A little light seeps in dustily between cracks in the boards, secondhand from a cobwebbed window somewhere across the cellar. In one corner of the little room a couple of mops, with stiff, clotted, foul-smelling heads, stand near a rusty bucket. The floor is dirt, a little damp to the touch, as cellar dirt usually is. The room is about three paces long and two wide, a mere broom closet or disused tool room. In the room a child is sitting. It could be a boy or a girl. It looks about six but actually is nearly ten. It is feeble-minded. Perhaps it was born defective, or perhaps it has become imbecile through fear, malnutrition, and neglect. It picks its nose and occasionally fumbles vaguely with its toes or genitals, as it sits hunched in the corner farthest from the bucket and the two mops. It is afraid of the mops. It finds them horrible. It shuts its eyes, but it knows the mops are still standing there; and the door is locked; and nobody will come. The door is always locked; and nobody ever comes, except that sometimes - the child has no understanding of time or interval - sometimes the door rattles terribly and opens, and a person, or several people are there. One of them may come in and kick the child to make it stand up. The others never come close, but peer in at it with frightened, disgusted eyes. The food bowl and the water jug are hastily filled, the door is locked, the eyes disappear. The people at the door never say anything, but the child, who has not always lived in the tool room, and can remember sunlight and its mother’s voice, sometimes speaks. “I will be good” it says. “Please let me out. I will be good!” They never answer. The child used to scream for help at night, and cry a good deal, but now it only makes a kind of whining, “ eh-haa, eh-haa” and it speaks less abd less often. It is so thin there are no calves to its legs; its belly protrudes; it lives on a half-bowl of corn mean and grease a day. It is naked. Its buttocks and thighs are a mass of festered sores, as it sits in its own excrement continually. They all know it is there, all the people of Omelas…They all know that it has to be there. Some of them understand why, and some do not, but they all understand that their happiness, the beauty of their city, the tenderness of their friendships, the health of their children, the wisdom of their scholars, the skill of their makers, even the abundance of their harvest and the kindly weathers of their skies, depend wholly on this child’s abominable misery”.

The excerpt above is extremely graphic, visceral and upsetting. It is also terrifyingly reminiscent of the conditions some innocent detainees are being kept in. Since before the seventh of October last year, the settler colony had already been imprisoning Palestinians without cause for indefinite periods of time. Some never to be seen again and all enduring inhumane torture. The foundations of a zionist city rely completely on the suffering and extermination of a native people, enabled and instigated by the Balfour Declaration of 1917. Zionism as an ideology is being upheld and maintained by some of the world’s most powerful leaders to this day. Its founding perpetrated by the British, who remain unshifting supporters of zionism, fearful to critique and address the genocidal intent of the settler regime whilst also ironically and insultingly sending small gestures of financial aid to the countries under attack by the weapons they are themselves providing the zionists with. It is stories like Le Guin’s which highlight the fact that to acquiesce to injustice is a choice, and that making such a choice means being entirely complicit.

So. In order to avoid acquiescing we must remain engaged, whether that be through investigation, discussion or stories. I hope this small snippet of Omelas can stoke a fire of curiosity within you, and incase you would like to read more I’ve linked the entire short story here.

For some further reading, listed below are some brilliant works by Palestinian writers that I’d encourage everyone to read:

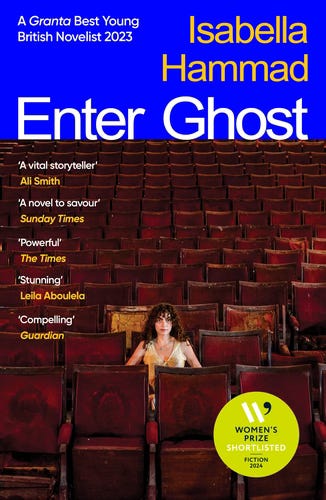

Enter Ghost - Isabella Hammad

‘After years away from her family’s homeland, and reeling from a disastrous love affair, actress Sonia Nasir returns to Haifa to visit her older sister Haneen. This is her first trip back since the second intifada and the deaths of their grandparents: while Haneen made a life here commuting to Tel Aviv to teach at the university, Sonia stayed in London to focus on her acting career and now dissolute marriage. On her return, she finds her relationship to Palestine is fragile, both bone-deep and new.

At Haneen’s, Sonia meets the charismatic and candid Mariam, a local director, and finds herself roped into a production of Hamlet in the West Bank. Sonia is soon rehearsing Gertude’s lines in classical Arabic and spending more time in Ramallah than in Haifa, along with a dedicated group of men from all over historic Palestine who, in spite of competing egos and priorities, each want to bring Shakespeare to that side of the wall. As opening night draws closer it becomes clear just how many violent obstacles stand before a troupe of Palestinian actors. Amidst it all, the life Sonia once knew starts to give way to the daunting, exhilarating possibility of finding a new self in her ancestral home.

A stunning rendering of present-day Palestine, Enter Ghost is a story of diaspora, displacement, and the connection to be found in family and shared resistance. Timely, thoughtful, and passionate, Isabella Hammad’s highly anticipated second novel is an exquisite feat, an unforgettable story of artistry under occupation.’

Minor Detail - Adania Shibli

‘Minor Detail begins during the summer of 1949, one year after the war that the Palestinians mourn as the Nakba – the catastrophe that led to the displacement and expulsion of more than 700,000 people – and the Israelis celebrate as the War of Independence. Israeli soldiers capture and rape a young Palestinian woman, and kill and bury her in the sand. Many years later, a woman in Ramallah becomes fascinated to the point of obsession with this ‘minor detail’ of history. A haunting meditation on war, violence and memory, Minor Detail cuts to the heart of the Palestinian experience of dispossession, life under occupation, and the persistent difficulty of piecing together a narrative in the face of ongoing erasure and disempowerment.’

Against The Loveless World - Susan Abulhawa

‘A sweeping and lyrical novel that follows a young Palestinian refugee as she slowly becomes radicalized while searching for a better life for her family throughout the Middle East, for readers of international literary bestsellers including Washington Black, My Sister, The Serial Killer, and Her Body and Other Parties.

As Nahr sits, locked away in solitary confinement, she spends her days reflecting on the dramatic events that landed her in prison in a country she barely knows. Born in Kuwait in the 70s to Palestinian refugees, she dreamed of falling in love with the perfect man, raising children, and possibly opening her own beauty salon. Instead, the man she thinks she loves jilts her after a brief marriage, her family teeters on the brink of poverty, she’s forced to prostitute herself, and the US invasion of Iraq makes her a refugee, as her parents had been. After trekking through another temporary home in Jordan, she lands in Palestine, where she finally makes a home, falls in love, and her destiny unfolds under Israeli occupation.’

Thank you for getting this far! I’d love to hear your thoughts on any of these stories and how you are remaining engaged with what’s going on. See you soon x